Perhaps it’s because I have needed to consult doctors and nurses recently. Perhaps it’s because there is one over-simplification about education that annoys me more than most others – the meme which unfavourably compares the relative use of technology in operating theatres and classrooms now and a hundred years ago. Perhaps it’s because I’m spending a lot of time working with the medically trained founders of adaptive learning company Area9 at the moment. But the use of medical language in the debates around the future of education seems to be growing, and doesn’t seem to be questioned very much. Whilst the analogy can sometimes be helpful, it can also be lazy, misleading and counter-productive – both as we think about teaching and learning, and about medicine.

One area where the medical comparisons are useful is when talking about the value of professional training. Most researchers agree with the not-exactly-controversial idea that teachers are the single most important ingredient in student success. It’s hard to argue differently about doctors and nurses in the treatment of patients. Yet in the medical world, continuing professional development is not only regarded as common sense, but in many countries it is a legal requirement. In formal education, not so much. A failure to provide resources, incentives and career pathways which recognise teachers as reflective professionals is, in my view, a glaring failure of many education systems around the world.

It also means we aren’t widely gathering evidence and reflecting on it to make things better. As Michael Feldstein recently wrote:

“…effective ed tech cannot evolve without a trained profession of self-consciously empirical educators any more than effective medication could have evolved without a profession of self-consciously empirical physicians”

Ah, “Researchers”. “Student success”. “Empirical”. Michael and I are of course adopting the language of “learning science” – the fraught and freighted sphere of establishing “what works” in education. And this is where the problems start.

Being empirical is relatively easy in medicine. People can be scientifically tested for the presence of ailments, diseases, pathogens and “abnormalities” within reasonable, globally agreed levels of probability. To caricature, you’ve got tuberculosis or you haven’t. Once the drugs have been administered, doctors and their managers can agree on whether or not the illness has gone.

Classrooms aren’t operating theatres. As I have written before, education is a world of values, subjectivity, and Politics (big “P” deliberate). Whilst most of the world can probably agree on whether or not three individual children from England, China and India can solve quadratic equations effectively, views on the “right” history of Hong Kong under the British Empire might be highly divergent. It’s very difficult to establish a definition of “success” here without acknowledging the (inevitable and necessary) value judgements which are involved. Which means a universal definition of “empirical” is often impossible. We all need to be honest about this, and devise intelligent ways to deal with it.

There’s also a more detailed debate about medical research methodologies being applied in education, thoughtfully covered by the UK National Foundation for Educational Research here, so I won’t go into detail. Whilst a randomised controlled trial (RCT) is the gold standard in the world of medicine, it seems it isn’t necessarily always the right way forward in education.

More interesting, perhaps, is a linked broader issue. RCTs aim to find drugs and processes which make people better – medicine, at least in conventional Western circles, is mostly a business of repair. In classrooms or educational systems, we probably shouldn’t be “fixing” people. We should be nurturing them to fulfil their unique potential and giving them tools for life (note the Western liberal assumptions here, naturally).

The description of some educational software as “interventions” is almost militaristic – implying a dramatic break with a present which is unsatisfactory. When governments and thought leaders start talking about education as “broken”, there are worrying implications of retrospective conservatism, rather than creative, hopeful imagination. When I’ve worked on successful educational resources, the process has been one of co-creation and discussion – something done with teachers, institutions, researchers and learners, rather than to them. Medical metaphors take us down a troubling road here, and it could be argued that the top-down “intervention” approach to improving education has seen some notable failures (inBloom’s collapse or Zuckerberg’s doomed initiative in Newark being good examples).

Then again, many major healthcare systems are now adopting the idea that theirs is not just a work of treating problems as they arrive. Living well, for a long period of time, can be seen as a partnership between medical researchers and the evidence they provide, trained reflective professionals acting as advisors and deploying the researched resources at their disposal, and patients taking responsibility for their own choices. A reflective, comparative discussion between health and education – about what they do and how they describe it – seems ever more fruitful.

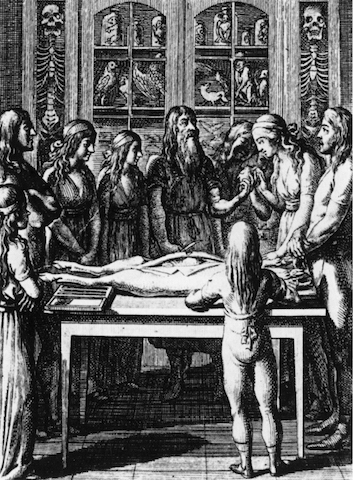

Image: Engraving by Daniel Chodowiecki from Franz Heinrich Ziegenhagen, Lehre vom richtigen Verhältnis zu den Schöpfungswerken und die durch öffentliche Einführung desselben allein zu bewürkende algemeine Menschenbeglükkung (1792). Wikimedia Commons/Public Domain.